Brushing away isolation

Loneliness, isolation are worsening mental health in seniors

Creating community and providing education can help deliver the solution.

For more than a decade, Karen Lee has fostered connections through stained glass, modeling clay, markers and more.

Lee leads Art Express, a program within the Smith Alzheimer’s Center at SIU Medicine that gives those with dementia a chance to express themselves without having to verbalize their feelings. On its face, it’s a valuable program as it gives those with dementia a better quality of life. It allows caregivers to breathe.

But from the beginning, a clear priority was providing a welcoming environment and bringing together a group of people often isolated. It’s mental health medicine in the form of a colored pencil.

You can see the spark in Lee’s eyes when describing how a new community springs forward as caregivers and patients form lasting bonds extending outside the two hours they spend together each week.

“‘Magical’ is the word that comes to mind,” said Lee, a University of Illinois Springfield instructor in the Department of Human Development Counseling. “When we talk about mental health, I thought, what is mental health really? There are many things I think that could define it. But one of them is being able to have a sense of connection and community.”

For seniors in particular, mental health decline can come from several factors, says SIU Medicine clinical psychiatrist Kalyan Kandra, MD. Seniors are more susceptible to life events that increase isolation, including declining physical health, financial burden, and loss of family and friends.

Alzheimer’s in particular paints a clear microcosm of the issue. Social isolation, loneliness and dementia are a vicious cycle as studies show that those socially isolated are at increased risk of dementia.

In fact, anyone who requires home health care is 3 to 10 times more likely to become diagnosed with major depression, according to the CDC. On top of that, addressing mental health is a harder conversation to have compared to younger generations.

“Most of the elderly hesitate to get help for depression and other mental health issues due to the stigma associated with mental health,” said Dr. Kandra. “They just don’t bring it up when they see their provider. The current generation is a little bit more open compared to the previous one, but there is still a lot more work that needs to be done.”

Caregivers not immune from depression

Caregivers are often just as isolated and a reported 15 million caregivers are over 65, according to the National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. Caregivers of those with schizophrenia or stroke are 20 to 40 percent more likely to struggle with depression. Fifty-nine percent of Alzheimer’s caregivers reported high to very high levels of emotional stress, according to Alzheimer’s Association’s 2023 Facts and Figures.

So not only is caring for another individual stressful, but isolation and burden affect the caregiver as much as the loved one.

“We had one caregiver who we interviewed early on in planning Art Express. She said, ‘Eventually friends, relatives, acquaintances, they stop coming around. Because they don't know how to respond. They don't know how to react or what to say. And they just stop coming around,’” said Lee.

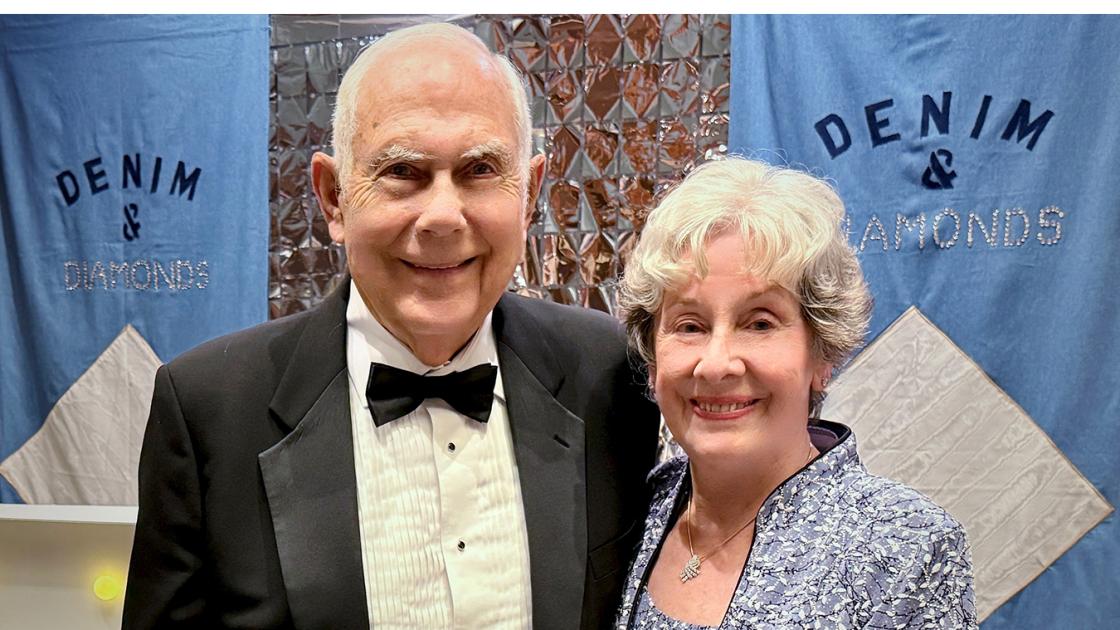

Roger Steinbach found himself in that caregiving role. Even being younger and more physically able than many other dementia caregivers, the emotional stress of having a professional provide some respite from his 24/7 care was difficult.

“I can’t reinforce enough how important it is to take care of yourself, not only physically, but mentally and socially,” said Steinbach. “Guilt was my worst enemy, feeling guilty if I had a couple of hours to myself to enjoy a movie, be with a friend or walk in the woods.”

First joining the Smith Alzheimer’s Center programs with his wife, Rhonda, Steinbach now volunteers his time to help others who are starting their dementia journey.

His advice: “Join support groups, there is nothing better than support from other caregivers. They may have the answer to your new challenge.”

COVID, lifespan intensifying the issue

Kandra echoes how powerful social interactions are. Paired with pharmacological interventions, physical activity and social connections are keys to improving mental health. That point was driven home in the past few years as COVID-19 locked down the community, seniors in particular, for extended periods.

Dr. Kandra’s recent research showed around three-fourths of respondents felt heightened levels of depression, anxiety and feelings of isolation during the pandemic. Notably, deterioration of mental health was not limited to those living alone in long-term care facilities. Individuals living with family members also experienced a decline in mental health.

"The pandemic's imposition of social isolation critically impacted mental health, particularly among the elderly, who constitute the most vulnerable segment of our population," said Kandra.

As we live longer, cognitive issues also increase. Case in point: The number of individuals expected to live with Alzheimer’s is set to nearly double to ~13 million by 2050. Kandra cited concern that the development of resources and education has not grown at nearly the same rate.

"With every decade, the risk of cognitive issues doubles, leading to a loss of independence and normal functioning,” said Kandra. “Consequently, these individuals become more reliant on others, driving up the care costs significantly.”

The need for a comprehensive educational framework for first-line providers is clear. A collaborative educational effort can pave the way for a more empathetic, informed and effective approach to elderly care, ensuring that our society honors and supports its aging members with the dignity they deserve.