Gene Brodland & the Power of Now

Happiness, worry, and how to use PBL to raise your kids

Happiness, worry, and how to use PBL to raise your kids

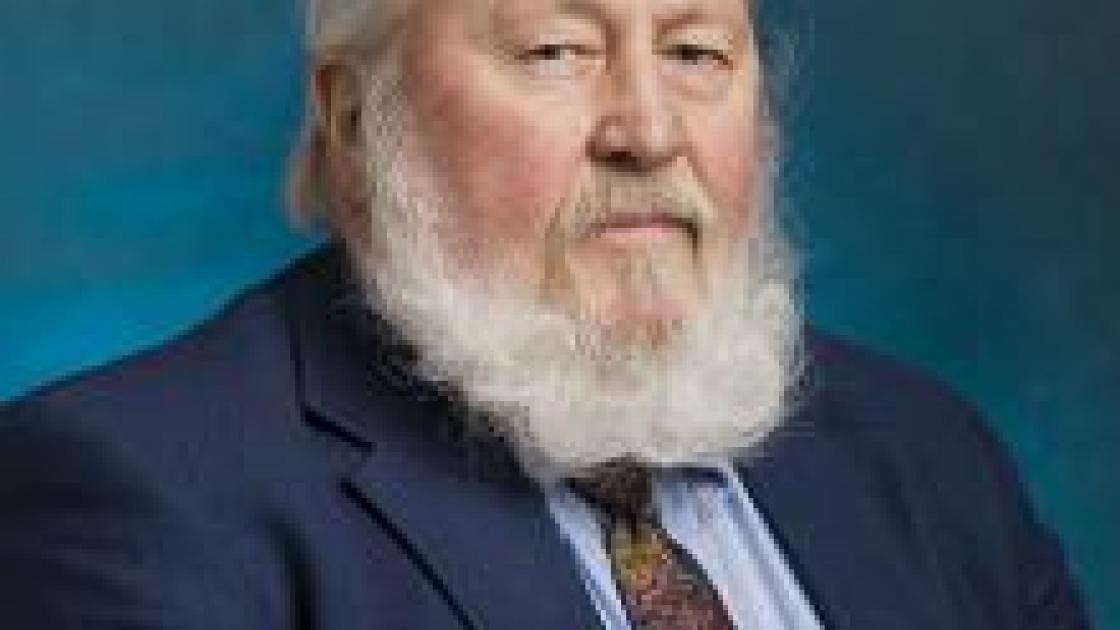

Gene Brodland was one of the founding psychiatry faculty at SIU School of Medicine. He passed away on September 7, 2020, at the age of 85. This article originally appeared in the summer 2010 issue of Aspects.

Written by Karen Carlson * photography by Jim Hawker

Gene Brodland hasn’t worried for 30 years. He’s an esteemed counselor, an accomplished tenor, a farmer’s son who has renewed his love of growing things. A husband, father, and grandfather, life is good for Brodland. So what’s he angry about?

“If I’m angry about anything, it’s people who are unhappy. I enjoy seeing people get better and be happy. As a counselor, my reward is people getting better.”

For nearly half a century, Brodland has helped countless adults and children achieve happiness. He recently was named Social Worker of the Year by the Springfield District of the National Association of Social Workers, named professional of the year by Cambridge Who’s Who for 2009-10, and included in Cambridge Publishing’s book Top 101 Industry Experts.

Brodland keeps a peaceful, cozy office at his private practice in Springfield. Surrounded by books with no computer in sight, he leans back on his chair and shares his story; his avuncular wisdom keeps an eager listener. His passion for helping people all started on his dad’s dairy farm in South Dakota.

“It’s lonely on the farm,” Brodland says. Young Gene watched his dad informally counsel fellow farmers. The farmers would sit in their cars, Gene’s dad reclining on the lawn. Quietly, they would sit and talk about their troubles. “Dad would send me away so I couldn’t listen in,” Brodland recalls. “I was always proud of my dad that people would turn to him.” The encounters sparked Gene’s seemingly simple, but ambitious life mission: helping others be happy.

Like many young adults, Gene considered other professions: farming, law enforcement and the army reserves. But he was drawn to helping people. He earned a sociology degree from Augustana College and a master’s degree in social work from the University of Iowa. Mentors helped him get experience in therapy, and with just two years’ experience, he became the first executive director of The Children’s Home of Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Brodland recalls it was a daunting task for a 31-year-old to manage the home’s day-to-day operations and oversee 18 adolescents. “When the kids ran away from the home at night, I’d stay up and pace the floor all night worrying if they were alright. I discovered that I was a chronic worrier, a trait I learned from my parents.” After two and a half years, he felt burnt out. “I did some soul searching and decided I didn’t want to do social work any more.”

From that personal crisis came his life-changing epiphany: to stop worrying. “When you worry, your mind goes way into the future — thoughts of ‘what if, coulda, shoulda woulda.’ I learned to pull my mind back to the present moment and force myself to stay in the present. I developed that before so many books were written on the subject.” It took time and discipline, but Brodland retrained his mind to stop worrying and live in the “now.”

With the flame of social work nearly burnt out, he rekindled his career with a love of academia at the University of Iowa working where for five years he worked with mentors, taught medical students and refined his skills in psychotherapy. “I’m interested in how the mind works,” he says. He is an advocate of biological psychiatry and psychotherapy, an interdisciplinary approach that attempts to understand mental illness in relation to the nervous system.

“The way you view the world affects your biology,” Brodland explains. Worry, distress, and stress can actually affect your serotonin and norepinephrine levels. Medicine does treat the biology of the disease, and then psychotherapy can help patients find effective ways of managing stressors in their life.” He cites studies that show psychotherapy combined with medicine is the most effective way to treat all mental diseases. “The relapse just on medication is 70-75 percent. The relapse with medication and psychotherapy is about 25 percent. You work with the thinking process as well as the biological process.”

A School of Medicine Pioneer

In the early 1970s, the newly formed SIU School of Medicine was building its Department of Psychiatry. Chairman and Assistant Chairman Ab Norris, M.D., and Terry Travis, M.D. recruited Brodland to SIU School of Medicine in 1972. Brodland joined as the third psychiatry faculty member in June 1973 and recalls being impressed with the dean, Richard Moy, M.D. “Dr. Moy gave a broad look at medicine and the far-reaching ranges medicine can have. He understood things from a scientific level and also a philosophical level.” At SIU, Brodland learned to write curriculum and enjoyed teaching medical students. “There was a lot of enthusiasm in the early days,” Brodland says, smiling with his fist in the air. “Everybody was saying, ‘We gotta make this go; we’re going to do something unique, something different.’ Building curriculum was quite a challenge. I don’t want to start another School of Medicine, but I’m sure glad I’ve been here.” He retired from the Department of Psychiatry as associate professor in 1990, but he retains a post as adjunct associate professor.

Today, he combines all his talents: He still sees patients five days a week working 7 a.m. to 5 p.m., counseling mostly adults either at the medical school or in his private practice with Bohlen and Associates. He also supervises a psychiatry resident in psychotherapy, and spends a half-day per week counseling children and adolescents in the Dept of Child Psychiatry at the Noll Pavilion. He specializes in numerous topics: alcoholism, marriage counseling, family therapy, drug abuse and gambling addiction. He has treated one patient on and off for 25 years. He recalls counseling one patient twice a week for 13 years.

Despite the demanding work schedule, Brodland, 75, says he has no plans to retire. “I’m not sure what retirement is,” he says with a laugh. “When you like your job, why quit? I’m still doing everything I like to do: working. It gives me an outlet for energy – and I’ve got a lot of it for an old guy.”

Indeed, he shows no signs of slowing down. Active in the community, he has been involved with Fifth Street Renaissance/ SARA Center since 1987. He helped create the first AIDS support group with Department of Medicine faculty Terry King in 1987 and the first local AIDS walk in 1994. The Fifth Street Renaissance/ SARA Center recently received $500,000 from the VA to build a homeless shelter for veterans in Springfield, to be completed next year.

He has a boundless energy for learning new things, evidenced by his desk covered in books reflecting his varied interests. A few of his top recommendations: The Four Agreements, Musicophilia, Toxic Parents, Developing Leaders, The Power of Now, and Failing Forward. He says he inherited his love of reading from his father. “Never stop learning,” says Brodland. His newest professional point of study is Asperger’s Syndrome.

Brodland and his wife of five years, Evie, share nine children and 30 grandchildren. His son, David, a 1985 graduate of SIU School of Medicine, is an accomplished dermatologist in Pennsylvania.

To ward off stresses in his life, Brodland can be found on his pontoon boat or taking a brief dig in his new garden, but his most rewarding outlet is in his singing. “Singing is like therapy for me,” he says. “Music was always a part of my family.” He recalls the whole family singing around the piano, his mother tapping on the keys. His dad was a singer in a quartet and a choir director in church.

For Gene, a 2 1/2-pack a day smoking habit clouded his resonant baritone voice. A heart attack in October 1987 persuaded him to quit smoking, and he has reaped the rewards in health, energy, and his voice. “I felt my voice improve. I could sing without coughing, and moved from a baritone to a tenor. Singing clears up my pipes pretty well.”

Friends and family call on Gene to sing at weddings and baptisms. But he most enjoys performing with his church or one of four choruses: the Springfield Choral Society, the Atonement Lutheran Church choir, the Land of Lincoln Barbershop Chorus, and the Jacksonville Symphony Chorale. “Singing is my catharsis; it’s how I relax and unload tension. After a two-hour practice, I feel refreshed.”

He’s partial to choral society music. This spring he sang the second and third movement of Handel’s Messiah with Jacksonville Chorale. He’s sung in cathedrals throughout Austria, Scotland and England, and Spain. Next year, Italy.

The energetic Brodland his roots planted firmly in the now. Here, he’s happy.

The Brodland Wisdom

ON THE POINTLESSNESS OF WORRYING

“People worry about the future and regret the past. To do that, you have to leave the present. Right now, right this moment, is the only thing we can be doing. Staying in the now helps us to interact more effectively. Living outside of now is really detrimental. We feel better in the present. You can’t change history, and you can’t control the future. It’s OK to plan, but don’t worry.”

ON HAPPINESS

“Find the happiness within you. Discover what gets in the way of your happiness. It can be your doubts, lack of self-confidence, your lack of self-esteem, your worrying habits, your regrets. All of these things contribute to unhappiness. Your self-confidence has to do with what you do, your self esteem has to do with who you think you are, your self worth has to do with how you think others value you; worry and regrets are big part of that. Getting those things out of you puts you in a better place.

ON PUNISHMENT VS DISCIPLINE

A 7-year-old boy named Randy taught me the difference between punishment and discipline. In 1964, when I was the administrator at the Children’s Home, Randy came into my office and said, ‘I can’t figure it out. You can ground me for the rest of my life, but it can’t make what I did go away.’ I decided we spend way too much time punishing people and not enough time disciplining people. Punishment is for what they did, discipline is for what they’re going to do. I’ve told parents: Don’t punish your child; use problems as a teaching moment. It’s like the Problem-Based Learning curriculum we wrote at SIU. When a Time-Out is needed, focus on discipline. I call it ‘Time Out With Purpose.’ Have the child think about what he or she can do to fix the behavior. When the child thinks of a solution, parents should discuss it with him or her. I began that idea 40 years ago thanks to Randy, and it still works today. Focus and intent of the discipline is vital for good behavior. If you don’t impart knowledge, they’ll make the same mistakes again.

ON SELF-CRITICISM

Over my 47 years as a counselor, I’ve found that people are very self-critical, which often comes as a result of their punishment as children. This is why I’m adamantly opposed to punishing children and insist on disciplining them.

We have critical notions about ourselves. We don’t allow for basic human error. I tell people, ‘You’ve never made a mistake.’ We don’t set out to make mistakes. Mistakes always occur because of lack of knowledge of how to do something. When mistakes happen we have two options – we can beat ourselves into the ground for being dumb and ignorant, or we can look at what we can do better in the future.”