Raindrops on a Tent - Deep Brain Stimulation

Deep Brain Stimulation brings new life to patients with movement disorders

Written by Rebecca Budde | Photographs by James Hawker

Published in Aspects, Winter 2012 | Vol 35-1

Diagnosed with essential tremor at age 10, Don Klinker of Decatur has always had a hard time with daily tasks that most people do without thinking. “I love to play golf,” says the 73-year-old father of four and grandfather of five. “But by the time I could take my hand off the ball, I’d knock it off the tee.” So his friends would tee up for him. And drinking coffee or signing checks? Forget it. He gave up coffee and had a name stamp made. Sometimes his wife or friends would do the writing for him.

But in February 2011, Klinker underwent an innovative surgery called Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) that he says has been “life-changing.” So life-changing that he had his second DBS surgery the following April. DBS offers hope for those like Klinker who suffer from movement disorders such as essential tremor and Parkinson’s disease. SIU School of Medicine’s Jeffrey Cozzens, M.D., professor and chair of neurosurgery, is the only surgeon offering it to patients in central and southern Illinois.

“Now I tee up the ball for a couple of the guys instead of them teeing up for me,” says Klinker, who estimates his symptoms have improved more than 90 percent since his DBS surgeries.

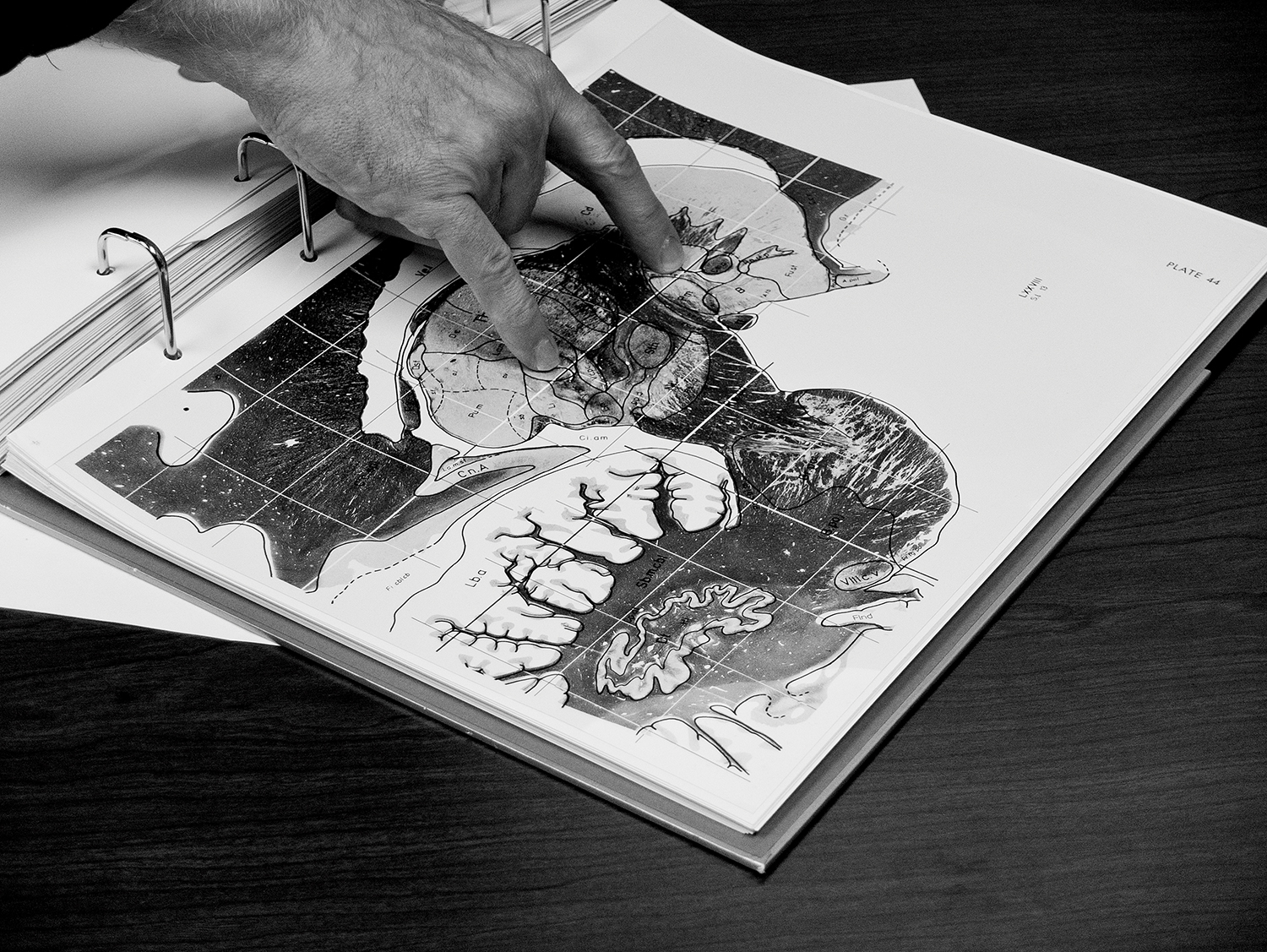

DBS is a stereotactic surgery that has been proven to significantly reduce the tremors and other symptoms for those who suffer from movement disorders. The surgery involves drilling a hole slightly smaller than a nickel into the skull. Electrodes attached to fine wires are inserted in the brain, usually in the subthalamic nucleus or ventrolateral thalamus, depending on the symptoms being treated. These wires are attached to a small stimulator, which controls the electrical impulses to the brain that help reduce the tremors.

DBS usually requires operations on both sides of the brain; however, the surgery is performed one side at a time with an approximate 6-week wait time in between. Since symptoms are not always symmetrical, Dr. Cozzens says that some patients see so much improvement with surgery on one side that it’s not necessary to operate on the other.

Deep Brain Stimulation was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 1997 for essential tremor and in 2002 for Parkinson’s disease. Studies since then show that the positive effects of the surgery are long-lasting. Diagnosed patients whose symptoms are not controlled well enough by the medication can be candidates for the surgery. However, not everyone with these conditions is eligible for DBS.

Dr. Cozzens has performed more than 350 DBS surgeries, most recently at St. John’s Hospital. He brought his skills with this innovative surgery to Springfield when he joined the School in February 2010. Though similar surgeries are being performed in the St. Louis and Chicago areas, “the only place that would have more experience is Cleveland Clinic or San Francisco,” claims Dr. Cozzens. Having this procedure available in Springfield means that patients don’t have to travel far to receive its life-changing benefits.

For more than 30 years, Dr. Cozzens has studied diseases of the brain and spine and has a special affinity for DBS. “These are the happiest patients I have. They’re thrilled to get their lives back,” Dr. Cozzens says. “They’re able to do things that they couldn’t do before.”

Dr. Cozzens isn’t alone in helping these patients improve their quality of life. He and the School’s neurology team work together to provide the best possible results for the patient. “Very few conditions can be dealt with by one physician,” says Rodger Elble, M.D., professor and chair of the neurology department and director of the neurology residency program. “Many diseases take a team effort because they are multifaceted. This is especially true with neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s disease.” Dr. Elble has assisted in all but one of Dr. Cozzens’s Springfield DBS surgeries.

For Dr. Cozzens, Tuesday mornings often begin in the operating room listening to the sounds of Louis Armstrong and Django Reinhardt coming from the small Bose speaker where he has docked his iPhone. He cracks some jokes and makes some small talk to lighten the mood as he begins to prepare the patient’s head for DBS surgery. Less than an hour later, the sound of jazz is replaced by quiet anticipation. Dr. Cozzens breaks the silence with, “We’re in.”

Under local anesthesia, the patient is conscious for most of the 7-hour procedure. This allows the team to interact with the patient so that they can determine the effectiveness of the electrode placement by monitoring the patient’s tremor and any side effects. Dr. Elble and Yen-Yi Peng, M.D., assistant professor of neurology, monitor the neural activity from the electrode that Dr Cozzens inserts into the brain. Dr. Elble examines the patient for improvement and side effects when the electrode is used to stimulate the brain.

Thomas Fearday of Teutopolis, 61, vividly recalls the procedure. Fearday had DBS on both sides of his brain — the first side in October of 2010 and then the other side in December 2010. He remembers Dr. Elble constantly moving his left arm and shoulder. “He could feel it loosen up when they got the electrode in the right place in my brain,” he says. “I heard static as they fine-tuned it to the right spot.” That static he refers to is the sound Dr. Cozzens calls “raindrops on a tent.”

Dr. Elble’s manipulation of the limbs ensures that the electrodes stimulate only the neurons that affect the patient’s symptoms. “It’s really important that we’re in the best possible spot, or it’ll be less effective when we stimulate, and more likely to produce side effects,” says Dr. Elble. The team works carefully to find the location that will have the most positive results.

Once the doctors find the precise location and the electrodes are placed, the patient is put under general anesthesia. A small stimulator pulse generator, much like a pacemaker, is then connected and placed in a pouch of skin just below the collarbone. The connecting cable is threaded to an area behind the ear where an incision has been made and then attached to the electrode emerging from the brain.

Though patients are understandably nervous about having brain surgery, they look forward to the results. “I was pretty shook up the night before the first surgery,” admits Fearday. But the second surgery two months later was much easier. “I was calmer. I knew what to expect.”

The risks of DBS — stroke, brain damage or infection — are rare; and according to Dr. Cozzens, even those who get an infection often want to have the surgery again. The results are that significant. “[DBS] can make them so much better and the results are so much better than using only medication,” says Dr. Cozzens.

A few weeks later at the post-surgery appointment, the neurologist adjusts the patient’s medications and stimulator to provide the best possible results for that person’s symptoms. “It’s exciting to see,” Dr. Elble says of the results of the surgery. “In the O.R. you can tell if you’re producing a beneficial effect, but you don’t really know the magnitude of the effect until you see the patient in the outpatient clinic and adjust the device.”

Fearday says that most of his progress came in the first two weeks after the surgery, but looking back over the year, he and his wife agree that his quality of life has improved tremendously. They are amazed at all that he can do now that he couldn’t before the surgery — drive a car and “even going to church on Sundays was getting to be really hard,” his wife notes.

“Now, I can go to family functions and not have to leave early. I don’t worry about freezing up when I go somewhere, and I can spend quality time with the kids and grandkids,” he says.

Dr. Cozzens’s youngest DBS patient was a man in his 40s. His tremors were so severe that he’d have a glass of water spilled by the time he got it up to his mouth. According to Dr. Cozzens, he couldn’t feed himself; he was losing weight and was unable to do many other daily activities on his own. “He was just devastated,” says Dr. Cozzens. “After the surgery, he was so much better, that he was out playing hockey!”

Fearday and Klinker aren’t rarities among DBS patients. According to Dr. Cozzens, approximately 80-90 percent of DBS patients notice some improvement in their symptoms, and about 70-80 percent notice great improvement. Some of the improvement is noticed quickly, while other improvements can be gradual. Fine-tuning the dosage of medication and the impulses of the stimulator can take some time.

The physicians caution that DBS does not cure Parkinson disease. “If you stop the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, people do pretty well,” says Dr. Cozzens. “But the disease can still progress.”

Investigations are ongoing for DBS in the treatment of depression, epilepsy, eating disorders, cluster headaches, chronic and phantom limb pain, Tourette syndrome, post-traumatic coma, memory disorders and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Dr. Cozzens is hoping for FDA approval to participate in a study that uses Deep Brain Stimulation for the treatment of morbid obesity. “Procedures for morbid obesity just try to fool the brain into saying, ‘don’t eat anymore.’ But if you can tell the brain directly not to eat anymore, that’s like the “holy grail” of deep brain stimulation surgery.”

With so many advances in neuroscience, Dr. Cozzens and Dr. Elble share a common goal for the future – a neuroscience institute. “I think we’re very close,” says Dr. Elble. “We’ve got a good team of neurosurgeons who do a variety of procedures that dovetail quite nicely with the interests in the neurology department.” Dr. Cozzens agrees that a neuroscience institute, which would include a neurosurgery residency program, is a priority. “We don’t want people to be forced to go to Chicago or St. Louis to get good neurological care,” he says. “We want to make Springfield a medical destination for neurological care.”

Fearday knows that coming to SIU to have his surgeries was the right decision. “Dr. Cozzens asked me if I could think of any reason not to have the surgery,” says Fearday. “I couldn’t, so I told him I would do it. I would never go back and NOT have it done. It’s been such a big change for me.” And to Fearday’s wife, it’s been “like a miracle.”

Don Klinker also knows about big changes. After nearly 62 years of living with tremors, he finally can do everyday tasks that most people take for granted. “After the surgery, when I was back in my room, they brought me some food,” says Klinker. “I took the soup in the spoon and held it there — still — and looked at it ... and I cried.”